Short Videos

See MoreCommunity

See MoreIndo-Canadian funds hurricane relief in Jamaica

The donation was directed to three aid groups supporting emergency response and reconstruction after Hurricane Melissa.

ADVERTISEMENT

Videos

View AllOpinion

See MorePeople

See MoreSt. Kate’s names Anupama Pasricha to leadership integration role

Pasricha, who currently serves as dean of the School of Business, will transition to the new role effective Jan. 5, 2026.

ADVERTISEMENT

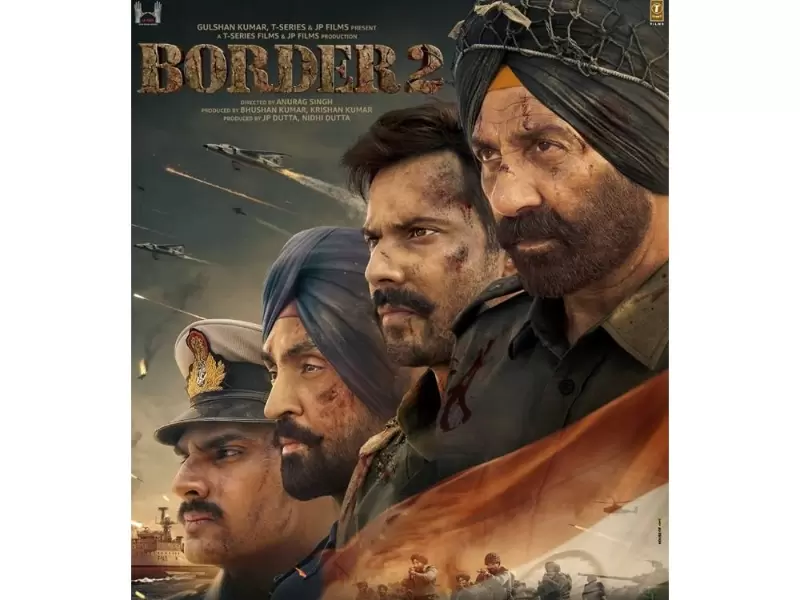

Entertainment

See MoreImmigration

See MoreFood

See MoreSPORTS NEWS

See MoreGreen made his IPL debut in the 2023 season after...

Messi was scheduled to land in the national capital earlier...

The Indian team became fifth nation to win a major...

Left-arm quick Arshdeep returned figures of 2-13 as India bowled...

.png)